Baseball Forecaster

How the Baseball Forecaster Happened

(Excerpt from Fantasy Expert, Chapter 5)

I was not a very good fantasy player in the early going, but I was convinced there had to be a way to win this game. Did I have to get a better handle on the player pool? Did I need to be willing to spend more for players? Or did I need to make better trades?

There were three books that had captured my attention… the Bill James Abstract, The Hidden Game of Baseball and How Life Imitates the World Series. I was convinced that the answer to winning this Rotisserie thing was hidden somewhere inside those three books. But Bill James, Pete Palmer and Thomas Boswell all used different metrics to evaluate talent. Which one was best – runs created, linear weights or total average? I thought it would be valuable to see all the players listed with those three “new statistics” presented side-by-side-by-side. I could put together a spreadsheet like that. Hmm.

I figured that if I spent the time to do that, maybe others would find it of value as well. What the heck, I’ll just write a book. How hard could it be? I had worked for several publishing companies. I had learned how to do direct marketing. I was a good writer and a magician with LOTUS 1-2-3. And I was a control freak.

Piece of cake.

Nearly four decades later…

Baseball Forecaster

The Complete Library

1986

Reports for all 26 teams, each listing the top 30 players. First publication of gauges from Bill James, Pete Palmer and Thomas Boswell, all in one place. Included secondary average, total average, linear weights, runs created, plus pitching effectiveness (forerunner of strand rate) and more.

1987

New: Offensive winning pct., defensive differential, baserunners prevented avg., earned runs prevented avg (next iteration of strand rate) and total pitching effectiveness.

1988

New: Expanded format, situational team records, monthly and 10-year performance trends, monthly Pythagorean projections, draft guide history (including the first player projections, for linear weights and Rotisserie ratings)

1989

New: xERA, team projections using Jamesian tools like the Johnson Effect.

1990

Long Ago in a Galaxy Far, Far Away

New: Expanded format, debut of the first individual player boxes. Boxes listed monthly stats in one section, 5-year stats in another, plus a 2-line commentary.

1992

Decomposing Idols and Near Sleep

New: Post-dating of editions begins, over 50% more players, revised player box format (including snapshot analysis section), major league equivalents, full stat projections, stolen base opportunity pct. and expected linear weights.

1993

Cocktails

New: Pure Pitching Potential (forerunner of BPV), more analytical essays (on predictability, forecast construction, leading indicators), burnout potential

1994

Harsh Realities

New: Full player commentary boxes, power and speed ratings, glossary

1995

Canned Philosophies

Published during the baseball strike. New: Forecast risk, strand rate

1996

Not all bad things happen in Pittsburgh

New: Normalized gauges, glossary expanded and redesigned into an encyclopedia

1997

Hillbillies

New: Minor league prospect analysis, base performance value (BPV)

1998

The Ancient Legend of TOG

No significant changes.

1999

Crickets

New: Runs above replacement, 2-year major league equivalent stats for all AA and AAA players

2000

Revelation

New: Injury updates, Low Investment Mound Aces (LIMA) Plan

2001

Propaganda

New: Walk rate, contact rate, expanded prospect summaries, Baseball HQ essay archive

2002

Catharsis

New: Pitching logs, Pure Quality Start (PQS) ratings, Domination/Disaster Pcts, full forecast boxes for top prospects, hit pct (H%) for pitchers, Cheater’s Bookmark.

2003

Pilgrimage

New: Bullpen indicator charts, ground ball/flyball ratios, expected batting average, 5-year platoon data, pitching run support

2004

Fanalytics

New: Batting hit rates, risk table, ERA/batting average percentage plays, closer volatility analysis

2005

Relevance

Advisors to the St. Louis Cardinals.

New: Reliability scores, DL days, ball-in-play rates, 5×5 values, new sections for Fanalytics and Gaming, redesigned draft guides

2006

Longevity

20th Anniversary Edition

New: Team section, 5-year DL history, stolen base opportunity pct., HR/FB rates

2007

WATCH

New: Expected HRs, league base performance indicators, gaming research, updated formulas, more ranking lists

2008

Noise

New: Expanded injury section, Japanese League coverage, breakout/breakdown scores

2009

Faith

New: More players, consistency charts, reliability grades

2010

Billboards

New: Mayberry Method, More years of data, batter BPV values, hidden contests and surveys

2011

Now

25th Anniversary Edition

New: Rotisserie 500, power and speed support charts

2012

Simulators

New: Expanded player boxes, expanded prospect section, universal draft grid

2013

Gravity

New: LIMA benchmarks, Mayberry Method 3.0

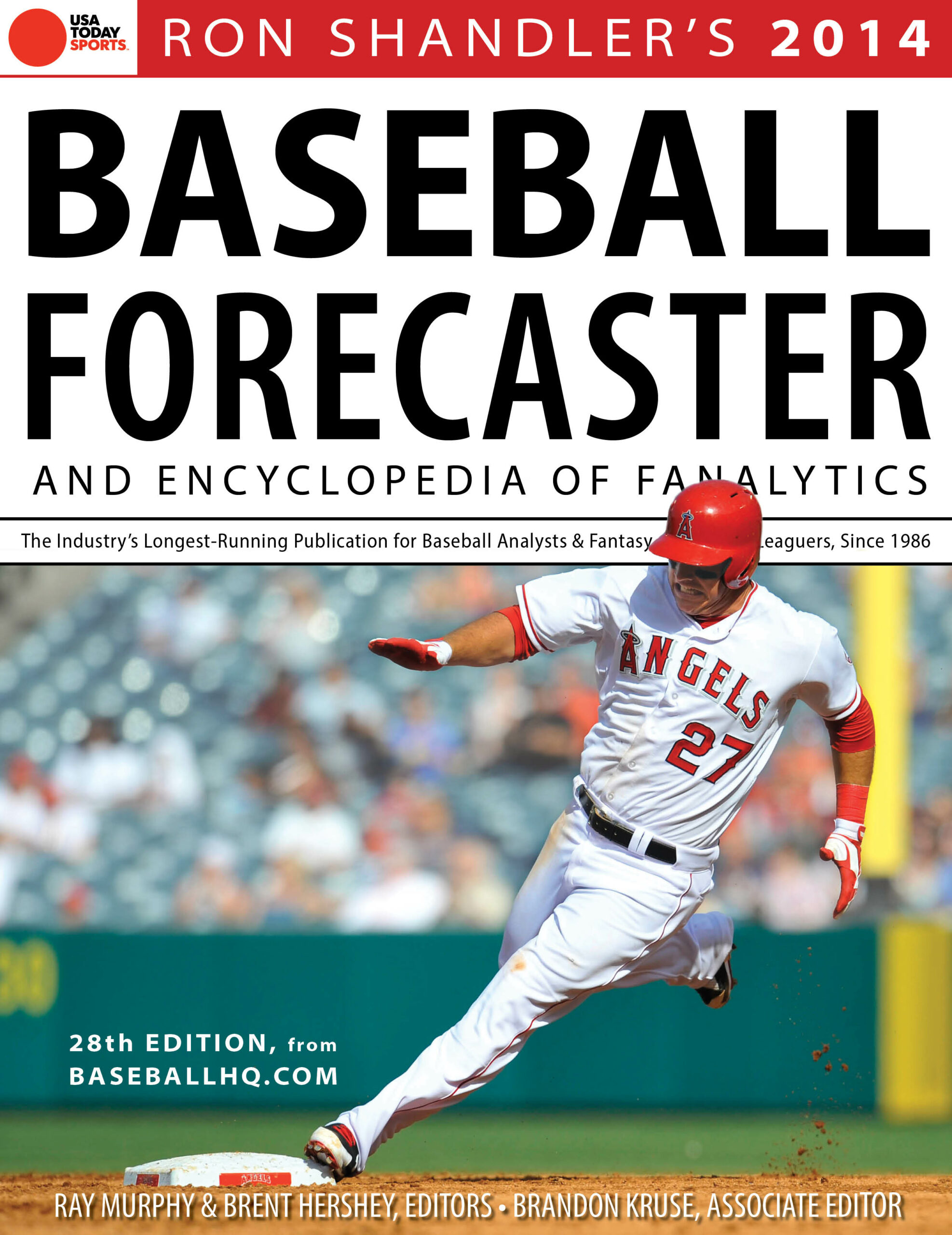

2014

Nightmare

New: Swinging strike rate, better platoon split data, updated formulas.

2015

Benchmarks

New: First round analysis, first pitch strikes, hard contact index, potential gainers and faders

2016

Segue

New: Daily fantasy support. B-list players, international prospects section

2017

Devaluation

New: Updated PQS formula

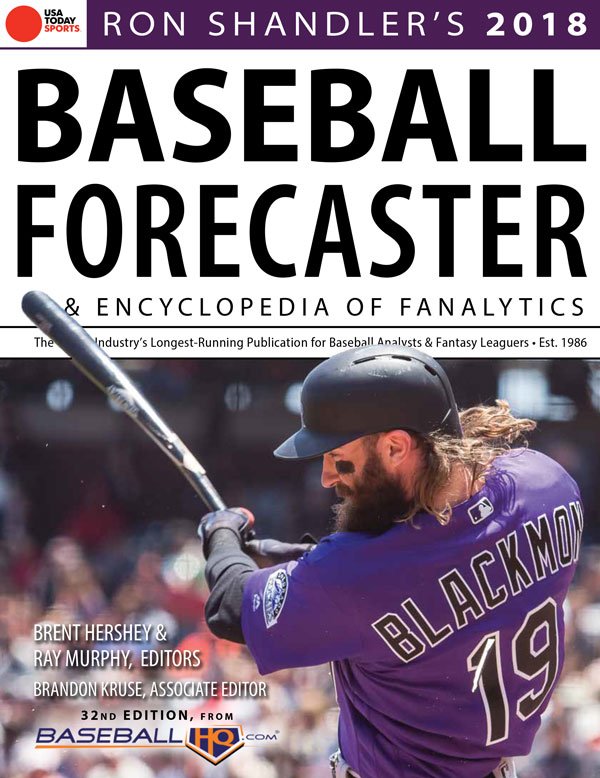

2018

Extremes

New: How to handle Shohei Ohtani, positive relative outcomes

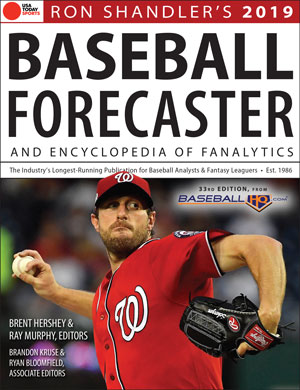

2019

Losing

New: Revised contexts in the changing MLB environment, fastball velocity

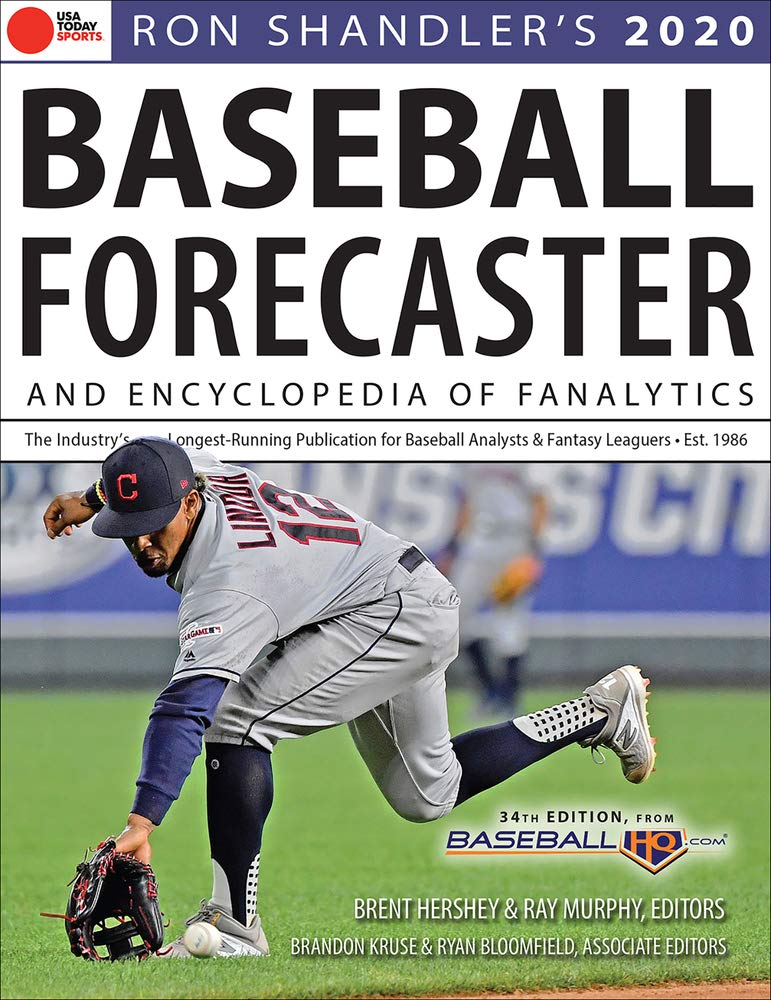

2020

Marketplaces

New: Plate appearances replaces AB, Platoon OPS+, xHR, xHR/F, xWHIP, Ball%

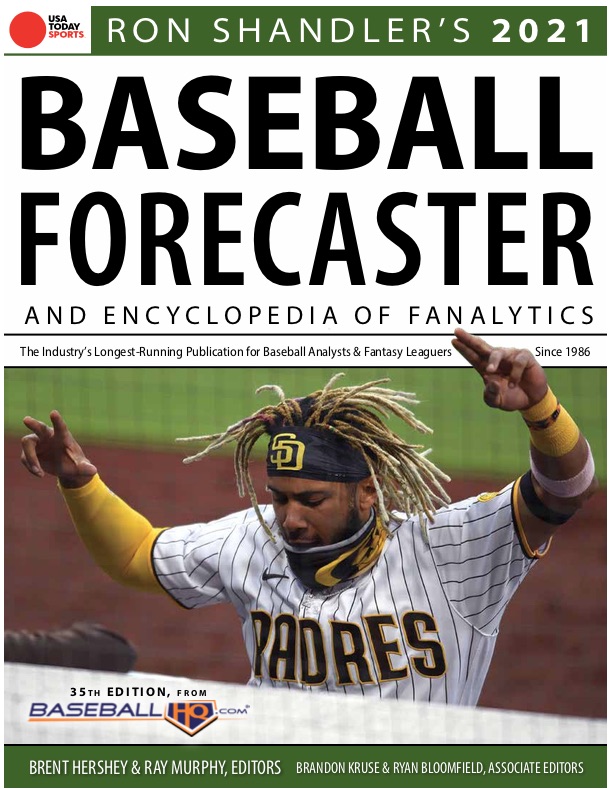

2021

Time

New: Percentage metrics (BB%, K%, etc.) replace /9 metrics (bb/9, k/9, etc.), QBaB, Barrel%, xSB

2022

Healing

New: xStats leaderboards, positional eligibility chart, head-to-head tools

2023

Phoenix

New: Updated LIMA benchmarks, normalized xHR, playing time metrics

2024

One-Off

New: Adjustments made for MLB’s new rules (e.g. new xSB calc, etc.).

2025

Anchors

New: The Broad Assessment Balance Sheet (BABS) comes home.